http://www.ancestry.com/wiki/index.php?title=Non-Population_Schedules_and_Special_Censuses

From Ancestry.com Wiki

This article originally appeared in "Census Records" by Loretto Dennis Szucs and Matthew Wright in The Source: A Guidebook to American Genealogy

In addition to the population schedules, federal, state, and local governments have used the census to gather special information for administrative decisions. These special schedules can be quite useful for family historians.

| Contents |

1885 Census

An act of 3 March 1879 provided that any state could take an interdecennial census with partial reimbursement by the federal government. Colorado, Florida, Nebraska, and the territories of Dakota and New Mexico returned schedules to the secretary of the interior. The schedules are numbered 1, 2, 3, and 5.

- Schedule No. 1: Inhabitants—Lists the number of dwellings and families. It also identifies each inhabitant by name, color, sex, age, relationship to head of family, marital status, occupation, place of birth, parents’ place of birth, literacy, and kind of sickness or disability, if any.

- Schedule No. 2: Agriculture—Gives the name of the farm owner and his tenure, acreage, farm value, expenses, estimated value of farm products, number and kind of livestock, and amount and kind of produce.

- Schedule No. 3: Products of industry—Lists the name of the owning corporation or i

The schedules are interfiled and arranged alphabetically by state and then by county. Schedules for a number of counties are missing. The National Archives has microfilmed the Colorado (M158, eight rolls) and Nebraska (M352, fifty-six rolls) schedules. The originals are in the National Archives. Individual, name of business or products, amount of capital invested, number of employees, wages and hours, number of months in operation during the year, value of materials used, value of products, and amount and type of power used.

- Schedule No. 5: Mortality—Lists the name, age, sex, color, marital status, place of birth, parents’ place of birth, and occupation, and gives the cause of death for every person who died within the twelve months immediately preceding 31 May 1885.

Research Tips for the 1885 Census

The 1885 census is useful for locating data about individuals who were living on rapidly growing frontiers: Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Nebraska, Florida, and North and South Dakota; for locating and documenting newly arrived immigrants from Europe; and for documenting businessmen and farmers—many of them immigrants—who were just getting started in their businesses. The manufacturers schedule (No. 3) for 1885 is the latest one available for research.

Mortality Schedules, 1850–1885

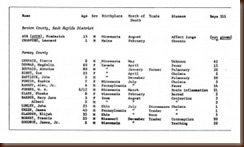

From Patricia C. Harpole and Mary Nagle, eds. 1850 Mortality Schedule, Minnesota Territorial Census (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1972), 100.

The 1850, 1860, 1870, 1880, and 1885 censuses included inquiries about persons who had died in the twelve months immediately preceding the enumeration. Mortality schedules list deaths from 1 June through 31 May of 1849–50, 1859–60, 1869–70, 1879–80, and 1884–85. They provide nationwide, state-by-state death registers that predate the recording of vital statistics in most states. While deaths are under-reported, the mortality schedules remain an invaluable source of information.

Mortality schedules asked the deceased’s name, sex, age, color (white, black, mulatto), whether widowed, his or her place of birth (state, territory, or country), the month in which the death occurred, his or her profession/occupation/trade, disease or cause of death, and the number of days ill. In 1870, a place for parents’ birthplaces was added. In 1880, the place where a disease was contracted and how long the deceased person was a citizen or resident of the area were included (fractions indicate a period of time less than a year).

Before the National Archives was established in 1934, the federal government offered the manuscripts of the mortality schedules to the respective states. Those schedules not accepted by the states were given to the National Library of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Copies, indexes, and printed schedules are also available in many libraries (see Mortality Schedule Depositories).

The United States Census Mortality Schedule Register is an inventory listing microfilm and book numbers for the mortality schedules and indexes at the Family History Library. An appendix lists where the records are found for twelve states whose schedules are not at the library. Originally compiled by Stephen M. Charter and Floyd E. Hebdon in 1990, the thirty-seven-page guide was revised by Raymond G. Matthews in 1992. The second edition includes twelve pages of introduction to this important material. While the reference is not available in book form outside the reference area of the Family History Library, the library has reproduced it on microfiche that can be borrowed through LDS Family History Centers and a few other libraries.[1]

Frequently overlooked by family historians, mortality schedules comprise a particularly interesting group of records. Over the years, many indexes, both in print and electronic have surfaced. Lowell M. Volkel indexed the Illinois mortality schedules for 1850 in Illinois Mortality Schedule 1850; for 1860 in Illinois Mortality Schedule 1860; and those that survive for 1870 (the 1870 mortality schedules for more than half of the counties in Illinois are missing) in Illinois Mortality Schedule 1870.[2] A more recent compilation is James W. Warren, Minnesota 1900 Census Mortality Schedules.[3] Ancestry.com offers a search of many of the available mortality schedules as part of its subscription service. As technology makes indexing projects more manageable, we can expect more of these genealogically valuable materials to be indexed.

Research Tips for Mortality Schedules

This table, originally found in The Source: A Guidebook to American Genealogy, shows where to find mortality schedules for various census years and for each state.

Mortality schedules are useful for tracing and documenting genetic symptoms and diseases, and for verifying and documenting African American, Chinese, and Native American ancestry. By using these schedules to document death dates and family members, it is possible to follow up with focused searches in obituaries, mortuary records, cemeteries, and probate records. They can also provide clues to migration points and supplement information in population schedules.

Revolutionary War pensioners were recorded on the reverse (verso) of each page of the 1840 population schedules. Since slaves were also recorded on the verso of the schedules, it is easy to miss pensioner names, especially in parts of the United States where few or no slaves were recorded. Also, many elderly veterans or their widows were living in the households of married daughters or grandchildren who had different surnames or who lived in places not yet associated with the family. By government order, the names of these pensioners were also published in a volume called A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.[4] The names of some men who had received state or Congressional pensions were inadvertently included with the Revolutionary War veterans. The Genealogical Society of Utah indexed the volume in A General Index to a Census of Pensioners . . . 1840.[5] These volumes are available in most research libraries. The attached image is the pensioner’s list for Maine.

The National Archives has the surviving schedules of a special 1890 census of Union veterans and widows of veterans. They are on microfilm M123 (118 rolls). The schedules are those for Washington, D.C., approximately half of Kentucky, and Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming, Indian territories, and U.S. ships and navy yards. Schedules for other states were destroyed in the 1921 fire that destroyed the 1890 population schedules. The schedules are arranged by state or territory, thereunder by county, and thereunder by minor subdivisions.

Each entry shows the name of a Union veteran of the Civil War; the name of his widow, if appropriate; his rank, company, regiment, or vessel; dates of his enlistment and discharge, and the length of his service in years, months, and days; his post office address; the nature of any disability; and remarks. In some areas, Confederate veterans were mistakenly listed as well.

Unlike the other census records, these schedules are part of the Records of the Veterans Administration (Record Group 15). They are discussed in Evangeline Thurber, “The 1890 Census Records of the Veterans of the Union Army,” National Genealogical Society Quarterly 34 (March 1946): 7–9. Printed indexes are available for some of the 1890 census, and Ancestry.com has indexed all of them as part of its 1890 Census Substitute.

Research Tips for Special Veterans Schedules

Revolutionary War veterans and military pensioners of Maine, 1840, in A Census for Revolutionary or Military Services (1841; reprint, Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1954), 1.

Veterans schedules can be used to verify military service and to identify the specific military unit in which a person served. A search of the state where an individual lived in 1890 may yield enough identifying information to follow up in service and pension records at the National Archives; it can often trace Civil War veterans to their places of origin. The 1890 veterans schedules have been indexed for every state for which schedules are extant except Pennsylvania.

A slave schedule from the 1860 census for Newton County, Georgia, listing the name of the slave owner, number of slaves, and each slave’s age, sex, and color.

Slaves were enumerated separately during the 1850 and 1860 censuses, though, unfortunately, most schedules do not provide personal names. In most cases, individuals were not named but were simply numbered and can be distinguished only by age, sex, and color; the names of owners are recorded. Few of the slave schedules have been indexed. See chapter 14, “African American Research.”

Agriculture Schedules, 1840–1910

Agriculture schedules are little known and rarely used by genealogists. They are scattered among the variety of archives in which they were deposited by the National Archives and Records Service. Most are not indexed, and only a few had been microfilmed until recently, when the National Archives asked that copies be returned for historical research. The schedules for 1890 were destroyed by fire, and those for 1900 and 1910 were destroyed by Congressional order. See the attached chart for the locations of existing schedules.

Research Tips for Agriculture Schedules

Agriculture censuses can be used to fill gaps when land and tax records are missing or incomplete; to distinguish between people with the same names; to document land holdings of ancestors with suitable follow-up in deeds, mortgages, tax rolls, and probate inventories; to verify and document black sharecroppers and white overseers who may not appear in other records; to identify free black men and their property holdings; and to trace migration and economic growth.

The first census of manufacturers was taken in 1810. The returns were incomplete, and most of the schedules have been lost, except for the few bound with the population schedules. Surviving 1810 manufacturers schedules are listed in appendix IX of Katherine H. Davidson’s and Charlotte M. Ashby’s Preliminary Inventory of the Records of the Bureau of the Census, Preliminary Inventory 161.[6]

The second census of manufacturers, taken in 1820, tabulated the owner’s name, the location of the establishment, the number of employees, the kind and quantity of machinery, capital invested, articles manufactured, annual production, and general remarks on the business and demand for its products. The schedules have been arranged alphabetically by county within each state to make research easier. The originals, deposited in the National Archives (Record Group 29), have been microfilmed with an index on each roll (M279, twenty-seven rolls). The Southeast, New England, Central Plains, and mid-Atlantic regional archives of the National Archives have copies of the series. These indexes have been compiled and printed as Indexes to Manufacturers’ Census of 1820: An Edited Printing of the Original Indexes and Information.[7]

No manufacturers schedule was compiled for the 1830 census. The 1840 schedules included only statistical information. Except for a few aggregate tables, nothing remains of these tallies.

From 1850 to 1870, the manufacturers schedule was called the “industry schedule.” The purpose was to collect information about manufacturing, mining, fishing, and mercantile, commercial, and trading businesses with an annual gross product of $500 or more. For each census year ending on 1 June, the enumerators recorded the name of the company or the owner; the kind of business; the amount of capital invested; and the quantity and value of materials, labor, machinery, and products. Some of the regional archives of the National Archives have microfilm copies of the schedules for the specific states served by the region.

In 1880, the census reverted to the title “manufacturer’s schedule.” Special agents recorded industrial information for certain large industries and in cities of more than 8,000 inhabitants. These schedules are not now extant. However, the regular enumerators did continue to collect information on general industry schedules for twelve industries, and these schedules survive for some states. The manufacturer’s schedules for later years were destroyed by Congressional order. See Summary of Special Census Schedules for the locations of extant schedules.

Social statistics schedules compiled from 1850 to 1880 contain three items of specific interest for the genealogist: (1) The schedules list cemetery facilities within city boundaries, including maps with cemeteries marked; the names, addresses, and general description of all cemeteries; procedures for interment; cemeteries no longer functioning; and the reasons for their closing. (2) The schedules also list trade societies, lodges, clubs, and other groups, including their addresses, major branches, names of executive officers, and statistics showing members, meetings, and financial worth. The 1880 schedules were printed by the Government Printing Office, and most government document sections of public and university libraries have them. (3) The schedules list churches, including a brief history, a statement of doctrine and policy, and a statistical summary of membership by county. The schedules for 1850 through 1900 are not listed in Davidson and Ashby, Preliminary Inventory of the Records of the Bureau of the Census. Those for 1906, 1916, and 1926 are printed; the originals were destroyed by order of Congress. Church records are especially helpful for researching immigrants, and the census of social statistics is a finding tool to locate the records of a specific group. See Summary of Special Census Schedules for the locations of extant schedules.

Special schedules are valuable because they document the lives of businessmen and merchants who may not appear in land records. If population schedules give manufacturing occupations connected with industry, search the manufacturing schedules for more clues. It is also possible to trace the involvement of an individual in a fraternal club, trade society, or other social group.

This chart, originally found in The Source: A Guidebook to American Genealogy, shows what special censuses are available in each state for select years.

- ↑ United States Census Mortality Schedule Register, FHL microfiche 6,101,876.

- ↑ Lowell M. Volkel, Illinois Mortality Schedule 1850, 3 vols. (Indianapolis: Heritage House, 1972); Illinois Mortality Schedule 1860, 5 vols. (Indianapolis: Heritage House, 1979); Illinois Mortality Schedule 1870, 2 vols. (Indianapolis: Heritage House, 1985).

- ↑ James W. Warren, Minnesota 1900 Census Mortality Schedules (St. Paul, Minn.: Warren Research and Marketing, 1991–92).

- ↑ A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services (1841, various years; reprint, Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1996).

- ↑ Genealogical Society of Utah, A General Index to a Census of Pensioners . . . 1840 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1965).

- ↑ Katherine H. Davidson and Charlotte M. Ashby, comps., Preliminary Inventory of the Records of the Bureau of the Census, Preliminary Inventory 161 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Service, 1964).

- ↑ Indexes to Manufacturers’ Census of 1820: An Edited Printing of the Original Indexes and Information (Reprint, Knightstown, Ind.: Bookmark, n.d.).

No comments:

Post a Comment